Malcolm "Mac" Rebennack, the musician most commonly known as Dr. John, is sitting in Louis Armstrong's living room. We're in Corona, Queens, where the legendary trumpeter's former home has been transformed into a historic site and museum. When asked about the two artist's shared history, Dr. John is predictably reverent.

"Louis was the master," he says. "I'm just a fart in the wind."

Rebennack and Armstrong both grew up in New Orleans's 3rd Ward, where they were at the forefront of two different eras of the city's rich musical tradition. Armstrong got his musical education in reform schools, riverboats, and the illicit hotbed of the Storyville district. His "Hot Five" recordings would become a high-water mark for early recorded jazz. Prior to his emergence as Dr. John, Rebennack operated in the seedy and rambunctious world of New Orleans rhythm and blues, gigging at strip clubs, playing sessions around town, scouting talent for independent label Ace Records, and circulating with the producers, musicians, and other characters responsible for pioneering rock 'n' roll.

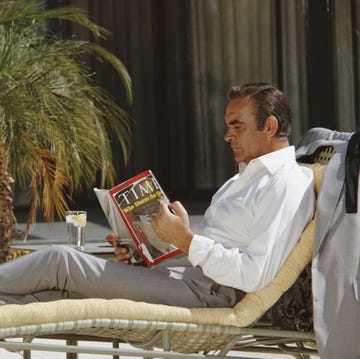

When Armstrong shot a pistol into the air on New Years Eve at the age of 12, he was arrested and sent to the progressive Home for Colored Waifs. There he'd find stability and along with it the beginnings of his musical education. Rebennack nearly had a finger blown off while intervening in a fight, rendering him better suited for piano than his original choice of guitar. The two later shared a manager, Joe Glaser, and ran into each other for the first time at his office in 1967. They would reminisce over a photograph on the wall there, of Armstrong in front of Ralph Shultz's Fresh Hardware Store, which happened to be across the street from the appliance repair shop. Nearly 50 years later, both artists are considered not only synonymous with New Orleans music, but with the city itself.

It isn't that surprising that Armstrong would visit Rebennack in a dream and instruct him to play his music. In 2013, he presented a tribute concert, "Props to Pops," much of which has been adapted for his new album Ske-Dat-De-Dat: The Spirit of Satch, which was released earlier this week. Band leader and trombonist Sarah Morrow arranged and co-produced the record, and many friends showed up to help, including Bonnie Raitt, The Blind Boys of Alabama, Shemekia Copleland, Nicholas Payton, and Terrence Blanchard, among others.

We talked to Dr. John about that dream and more at Armstrong's former home.

ESQUIRE.COM: Is this a good spot to talk?

DR. JOHN: As long as I can bust up a cigar, I'm happy.

ESQ: Tell me more about the dream where Louis came to you.

DJ: I'd never thought I'd see Louis in a dream, that's the last place I thought I was ever gonna see him. He said, "Do this record… your way." And that was like an order. And I mean, I felt that. Somewhere in the spirit gig, he's there.

ESQ: You ended up doing songs that span his entire career, from the Hot Fives to his later popular hits. Why did you approach it that way?

DJ: I took everything that he would've pulled in. I tried to put everything that was fresh into the game. That's what I told Sarah when she was writing the charts and producing this record with me. I said, you gotta keep everything fresh.

ESQ: How do you hold Louis in your mind, in terms of him as a man and an artist?

DJ: I just think the world of him. My pa used to sell records on Gentilly Road, right by Dillard University. That's not too far from the Milne Boys Home. I used to hear Louis's records and some Afro-Cuban records and I'd hear some bebop records, like early Miles Davis and Horace Silver. There was a lot of stuff that Louis did that struck me. And it was a lot of the early stuff. That was the shit that took me out — there was something about that Hot Five. It was badass. That's the records that stuck out to me. I knew they was dated, but I knew that they was slammin'.

ESQ: I think there are a lot of interesting parallels to your lives. Do you feel that way?

DJ: I probably got shot at a lot more, but the fact is that he was spiritual, and a thing in my spirit. Even though my pa was "Kid Ory this, Kid Ory that," he wasn't my favorite trombone player. But that was all right, I loved the cat too. I liked Frog Joseph [of the Original Tuxedo Jazzband]. Now his son Kurt is playin' tuba really good.

ESQ: He grew up impoverished; your family was a working family, middle class, but in the same neighborhood. What do you remember about the character of the 3rd Ward when you were growing up?

DJ: I always remember this lady, I was crossing the green, going to the other side of Jefferson Davis, and this lady said, "That boy there," she said, she was talking to the police. She said, "You're a dirty, dirty people." That lady lived downstairs from a bar, and she was pointing at me and saying that. Her husband used to beat the hell out of her every night. And then he'd come out of it and make it up with her or something, I guess.

But you know, I remember my pa used to have me get the river rats out the basement, and they was always in our basement. I would hit 'em with a shovel or something and try to take 'em off the count. One of 'em didn't work and I went and got my 410 Over and Under and fired it, and shot that rat right through the wall! And I was thinkin', oh boy I'm gonna be in some trouble now. I was in trouble when my pa got home. In fact, I was in trouble when my grandma got home. But that's a different time zone, back in those days…you know.

...You working for Ex-quire?

ESQ: Yes, why do you ask?

DJ: I think they had me supposed to do a thing with a girl from there a long time ago. My last guitar teacher, Roy Montrell, was in Vegas with Fats Domino's band — no, maybe he was there with somebody else — well, whoever he was there with… But anyway, the weirdest thing is this: He says, "I told y'all to hear the Elephant Legs!" He's talking about me. I was supposed to take this picture in the lobby of a Las Vegas hotel. But that was for Ex-quire. I just have a memory of that weird thing.

ESQ: Another parallel I saw is as an ambassador of New Orleans music. Do you think you share that kind of role with him?

DJ: You know, I never think about shit like that. I know Louis did that. He was the ambassador to the world from New Orleans. And that was a blessing, and I'm sure that Joe Glaser had something to do with that. But the little time I knew Joe, it was weird.

ESQ: Anything surprising when you met him?

DJ: One of the things that really drew me a great picture of the brains was like this: I knew that there was a thing about the days he came up. I remember I had Mr. Google Eyes [R&B singer Joe August, who had an affinity for ogling women] bring Dizzie Gillespie to a gig. Dizzy said he thought Louis was an Uncle Tom. And I said, I don't think so. And Diz said to me, "I got your point, Google Eyes made it clearer." And that was something that meant something to me about Louis. 'Cause I knew in my spirit that he wasn't a Tom, he just came up in that time zone when if he was gonna be workin' in the white man's world, you had to do shit. And that was a good thing. But it surprised me, when I told Louis something about that, and he said, "Thank you. " He just was very gracious about it. That was a side of him I had never seen before.

ESQ: Armstrong was very big-hearted and internally driven.

DJ: He was the real McGillicuddy. He could play his ass off. He always did.

ESQ: One other thing I think you two have in common is a way with language. The song "Sweet Hunk O'Trash" with Shemekia Copeland has some great dialogue.

DJ: That's what I was trying to get across with that record. My spirit was in a zone. I knew that Sarah would do some slammin' charts, but I didn't expect all of what she wrote. But boy, she not only did that, she produced a helluva record with it, I think. I feel that in my spirit. It's probably one of the records I'm most proud of, you know? 'Cause I believe I had some good things to work with. That's a special thing. It wasn't just Louis.

ESQ: You mention hearing Armstrong's records and appreciating them when you were a kid. Was he an artist who was with you all this time?

DJ: When you're from somebody's neighborhood and your pa says, every time you pass it, "That's where Louis Armstrong was born," you get a feelin'. You know how much your pa really loved this cat.

Something else we did in common was we hired the musician we thought was best for the gig. And it didn't matter if it was a kid or any other cats he had playin' in the band. I felt like I've always tried to do that. And that's something good. I feel that in my spirit.

ESQ: Music was able to carry you both through some tough times.

DJ: One of the best pieces of advice my pa ever gave me, he said, "Kid, you got kicked outta three schools. My advice is to go on the chitlin' circuit with them old men." And that was the best thing I ever did. Even though it was not the best thing in some ways, it was great. But at least I had a pa. Louis didn't have no kinda dad. That was something we was talking about in Joe Glaser's office one time. He said, "You're lucky you had a pa that gave you some good advice." And I was. I think King Oliver was his father figure. I really believe that from my spirit because I know he loved King Oliver. And that's what got him on the road.

ESQ: New Orleans musicians in Armstrong's time were affected when Storyville was shut down. You had a similar experience when New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison cracked down on nightlife.

DJ: I hate politicians. One of those stupid mayors of New Orleans tore Louis's home down. What a bunch'a idiots.